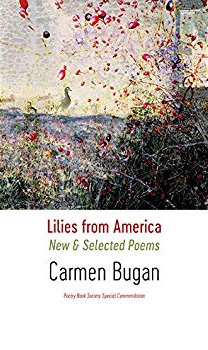

Lilies from America, New and Selected Poems

Lilies from America, New and Selected Poems by Carmen Bugan. Bristol UK: Shearsman Books, 2019. 115 pp. $17. (paperback)

My father liked to quote Lin Yutang, a popular sage of the 30’s: “Patriotism is the memory of the good things you had to eat as a child.” In this sense, the Romanian-born poet Carmen Bugan is a patriot, though Lilies from America, her collection of new and selected poems just out from Shearsman, never waves the Romanian flag.

It’s a complicated relationship. During the 70’s Romania had prospered while pursuing foreign investment and technology. Then, during Bugan’s childhood, Ceausescu, overwhelmed by the global oil and debt crises, made the irrational decision to pay off the debts quickly. According to Alexander Clapp: “To do so, he slashed imports and investment to the bone in a manic austerity programme, the most disastrous episode in the economic history of postwar Europe. Virtually overnight, Romania reverted to a subsistence-level peasant economy. (Clapp, New Left Review Nov-Dec 2017).”

This is the context for Bugan’s agrarian memories and her father’s one-man war against Ceausescu’s state, which landed him in prison and exposed his family to privation, harassment, and brazen surveillance. Carmen and her family were forced into exile in Michigan: “You awake without a country, a house, /… your / Host speaking to you in an alien language.” (p. 24)

That language would not remain alien. Bugan went on to receive the Hopwood award at the University of Michigan, a Ph.D. from Oxford, and recognition for her poetry, criticism, and her memoir Burying The Typewriter, nominated for an Orwell Prize. Yet—as Dante is told: “You shall leave everything you love most dearly: this is the arrow that the bow of exile shoots first”— Bugan has carried with her the loss of those dearly loved things.

She has set herself the task of preserving her Romanian childhood, the pleasure and the pain, fashioning a style influenced by Heaney, Milosz, Mandelstam, Brodsky, and Herbert, a style that records and observes—but reveals its own engagement. In particular those things “you love most dearly” appear before the reader: “Then in a new white case we stuffed fresh hay; / After she sealed it, she summoned us to dance / The hora on top to even out the surface.” (p. 46)

I think she wants to say: I/we are Romania—not you. The you is the secret police, the Securitat. But she avoids the dangers of ideological poetry and the romantically embellished style of conservative Romanian writers like Eminescu, the national poet. After all, before the communists came the Iron Guard, a native fascist movement popular with intellectuals who fashioned a grandiloquent idiom, a spiel of nationalism, religion, and sacrifice. To Mircea Eliade, the famous theorist of religion, the Iron Guard (first called Legion of the Archangel Michael) “… is so profoundly mystical … that its success would designate the victory of the Christian spirit in Europe. ” (quoted in Clapp, op. cit.) Bugan rejects such high-flown mystification, choosing the eloquence of clarity and integrity—integrity meaning truthful, just, but also durable, sound in construction—a soundness attained by stripping the verse down to pictures and events given solidity by sensory details. Her mantra might be “No patriotism but in things”—things turned into images cut on a printer’s block.

Imagist would be my word for Bugan’s style if the term carried less historical baggage. The images tell a story, but through parataxis, so that a resonance adheres to each act or picture—linden tea, sister, aunt, sunflower, “Grandmother hovered over polenta /

With the wooden spoon, while buttermilk, / Aged in earthen jugs, was ready to be poured” (p. 50). Against the abstract memes of ideological nationalism—motherland, fatherland, or the Sacred Soil of the Nation—these poems set Mother, Father, or “‘The earth will remember you,’ my grandparents once said.” (p. 61)

A contrast with another writer exiled by Ceausescu may be relevant. Herta Muller, winner of the 2009 Nobel Prize, was born in a German-speaking region of Romania, learning Romanian at university. She has attributed her surrealist style to her numerous interrogations by the Securitat, with whom she is still at war—“Ceausescu was mad and he made half of Romania mad,” she says (Guardian Interview, Nov. 30, 2012). “I'm mad because of him.” Anxiety, anger, alienation—hard-earned— run through her work.

Like Muller, Bugan got her family’s file from the Securitat—transcripts of wiretaps, reports by agents and neighbors. For Muller, this was a nightmare of paranoia and betrayal. Bugan was also appalled; and yet, in the records of her family’s trauma she found images of strength, love, and courage. In “Their Way,” Bugan tells a story from the archives, a story she had not known. At a time when “I knew them mostly fighting with each other / bickering like kids at school,” her father tells her mother that people kept asking what train he would take, when he would return. They know this to be the Securitat. Thugs may be sent from Bucharest to assault him. Without hesitation the mother speaks: “From today onward we go together to / the train station …” (p. 78) Bugan understands well how bravery and love are seen to best advantage standing on their own, without flourishes. “October 26, 1988” presents an adolescent girl’s desire to be a heroine: “I said to my father that I would have saved him / From going to prison if I could’ve been his lawyer” (p. 83), a forgotten moment preserved by the enemy.

I especially liked a poem called “Evening.” A stork flies home with a snake in its beak, a familiar image in that part of the world and a spiritual symbol found in Byzantine mosaics. A little girl finds her black-suited grandfather behind the house, amid fireflies. The poet sees it as a painting: “Tall at the stove in the garden, fire…framed by a purple sky and rows of quinces. / You stand next to a tree with a stork at the top. / I step into the canvas / A child with uncombed hair” (p. 41). Mysterious and endearing.

Lilies from America also features poems drawing on the writer’s life in the West. Without the drama of the dissident’s ordeal or the evocation of a pastoral world, these poems are quieter, but the continuity is clear—the pain of exile, loyalty to family and friends, who are always present, at least in the poet’s mind. Even when a young woman wanders alone in a series of short poems about hiking the Dorset coast and the writing looks more typically Western—it isn’t. Less egocentric, less mannered, the poetry allows a steady, generous view of children and the natural world, as in “Mating Swans” (54), elegant and discreetly erotic.

One of these post-exile poems, “The House Founded on Elsewhere,” longer and more discursive, calls for special notice. In it, Bugan steps out from the wings and speaks to the questions at the heart of her poetic persona. It begins with an epigraph from the Romanian/Parisian writer E.M. Cioran, famed for his aphoristic fragments exploring nihilism, despair, and decay: “He who turns against his language, adopting that of others, changes his identity and even his deceptions. He tears himself—a heroic betrayal—from his own memories, and up to a point, from himself” (p. 89). Divided into 7 sections, the poem begins at the shore where identity can float like a cloud in the shifting landscape which, nevertheless, sends an obscure message to “Those without a home.” The following two sections develop an extended metaphor—in a house built with words “bought / At the price of exile,” the poet notices a crack. She tries to paper it over; it spreads. The solution is to expose “the foundation of elsewhere,” meaning her Romanian material, and to rebuild the wall with elements of past and present together. I assume this refers to the recovery of her family files from State Security. In a University of Michigan podcast (“Carmen Bugan and the Language of Freedom,” RC Podcast, 8/1/19), she calls the Security Files a “scar,” a “wound.” But confronting them gave access to speech and images which strengthened her work. The poem’s final section meets the Cioran quotation head-on:

Not all the words you say are the Self and not all turning

Against your language is self-betrayal. Behind each word

Is what tries to get inside it. That is what matters.

Whether I speak it in my own language

Or in the tongue of others. The thought, the breath

With which you send love out, or forgiveness, say,

Outlive the words and languages, … (p. 91)

This seems direct and authoritative. Sections two and three, the allegory of the crack in the wall, don’t work so well. Perhaps they are too discursive. The emotional self-possession, so notable elsewhere, becomes a little slack here. And yet, “House Built on Elsewhere” is a rich ambitious piece, with much thought and experience behind it.

It is not typical of the book’s prevailing style, however; for what I feel most in these poems is an earnest voice, quiet but determined, taut with the discipline to sail past temptation, like Odysseus among the sirens—temptations to lose one’s self in lamentation, accusation, revenge.

Rather, Bugan would find language to keep people and moments alive.

—Lem Coley reviews occasionally for The Manhattan Review. He retired from Nassau Community College and currently works as a home health aide while his wife recovers from a knee replacement.