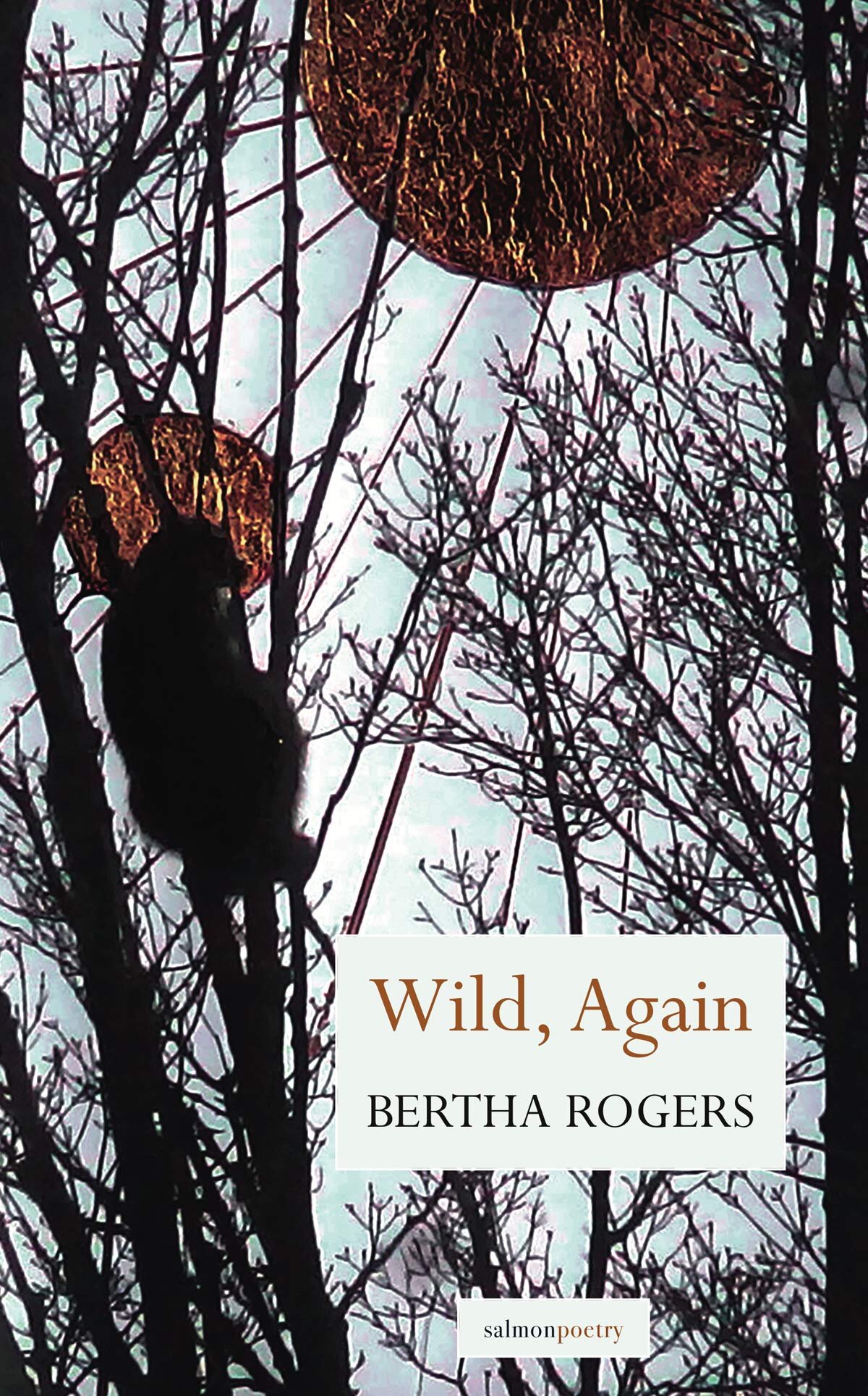

Wild, Again

Wild, Again by Bertha Rogers;. Salmon Poetry, 2019, 109 pp. $14.95 (paperback)

The natural cycle has a way of asserting itself. Just a year ago, it seemed as though all of life were being reduced to bits of data. One way or another, much of what we did and said was being conveyed by bits and then sliced and diced as bits in the digital marketplace we euphemistically refer to as “social media.” The bits, it appeared, had taken over.

But there were also bats – and soon life on every continent was reshaped by man’s interaction with a species most of us seldom think about. Lives abruptly ended, careers stalled, schools and work places were shuttered, all because humanity had put the bat population under pressure, and, unwittingly but most effectively, bats had pushed back. Nature, it turned out, was still there, out beyond our transponders, and, as always, its agenda did not defer to ours.

Bertha Rogers’s new collection, Wild, Again, gathers more than five dozen widely published poems that were written before humanity’s current crisis but now seem deeply relevant to our new way of living. They are daringly and fervently engaged with the natural world – through observation and through active and imaginative participation. "Holy Beast," the book’s first poem, begins with these lines:

Once I was part of a holy beast, I was.

I was a dog, a bear, a horse.

I was the leader and the dragging-led.

My fur was both sleek and shaggy, black and white.

I was tall as a stallion, long-maned,

yet bony, as deep withered as a dog.

I barked and I whinnied, I growled.

I cantered and I loped, I lumbered.

One of the reasons Rogers can write so confidently about nature is that she lives in Delaware County, one of the most bucolic parts of the Catskills –a place of companionable, rolling hills covered with maple, beech, oak and the occasional evergreen. The area’s landscapes were made famous by the writings of John Burroughs, born in nearby Roxbury. When John Lennon and Yoko Ono searched for a dairy farm to be their summer home, they picked one in Franklin, not far from where Rogers lives.

But these poems have more in mind than quietly contemplating rural life, though some of them do that nicely. Those surprising statements in the opening poem lay down a kind of challenge. How will the rest of the book justify these displacements of the self? And if so, what should we make of them, emotionally and aesthetically?

If there is a guiding principle throughout the collection, it seems to be the opposite of the pathetic fallacy. Rogers usually avoids projecting her own concerns on the natural forces around her. Instead, she gives voice to the impulses behind those forces – not to mythologize them or identify with them, but to try to understand them in the full context of their non-human reality.

In “Stone and Stand” that first poem’s desire to inhabit elements of nature extends to inanimate objects, and a more playful, aspirational tone emerges:

First, I was mountains, one among

many – our shoulders shoved up, rough.

We jostled and pushed, seeking blue . .

Then I was stone, alone. I stood

in a green field, below a flimsy sky.

I was hugely still. There was quiet

around, within – just air and I.

What a feat: to make us feel the kinship between the silence of a landscape and the deeper stillness inside a stone! The unexpected rhyme, in a poem otherwise woven together with assonance and consonance, is delightful.

Rogers’s imagination is so quick and fertile that it even finds delight in describing the things that we, as human beings, can’t do, as in “Compensation”:

Because you and I will never be bird,

because we will never, glancing downward,

lift furled arms, invent wings; never tuck

taloned pins under feathered tail, nor feel

the stipstream against flensed eyes; nor know the close

admiration of sun against clouds’ supple

surfaces; the safety of plumes in rain –

Sometimes Rogers writes a more traditional kind of pastoral verse, as in a pair of facing poems that are among the finest in the book. “Planting Wildness” celebrates the planting of spruce seedlings on a mountainside and watching them grow over a period of fifteen years: the delicate young trees the speaker once planted are now large enough to walk under. Participating in that re-covering of the mountainside is seen as a good reason to lift one’s head off the pillow in the morning and drop off to sleep each night, “Even when/the bleakness is hard upon you.”

In the facing title poem, "Wild, Again," the speaker views that reforestation in a longer timeframe. It’s a part of a larger process that has often occurred in rural areas of the northeast United States: the transformation of first-growth forest to field or orchard and then, in some cases, back again to forest. The speaker describes a once active dairy farm, complete with dogs to corral the cows and wild strawberries among the grasses, now replaced by a forest of spruce trees, in which the wind and a new inhabitant move:

Ah! Wind soughing, susserating—

and not just there, the doe’s immigrant

eyes – home, again, in her found wild.

Rogers employs a wide variety of forms; she is equally at home in the short-lined verse of “On North Mountain” or the relaxed pentameter of poems such as “Luna.” Sometimes, as in “Wrong Way,” she uses alternating voices, or seems to improvise, as in the wry humor of “The Cat in the Diner.” She even casts her lines in unrhymed sonnets, like “Oriole” and “Stone Cold,” and gives us a villanelle in which the tight verbal pattern acts as a foil for words that “speak, then slip away.” None of this is idle virtuosity: her easy movement among verse forms seems required by the free-ranging progress of her thoughts.

Several of the poems here enact Rogers’s struggle to come to terms with the death of her husband, Ernest Fishman, with whom, nearly three decades ago, she established Bright Hill Press and the Literary Center of the Catskills in Treadwell. (Rogers continues to serve as editor-in-chief of the press.) One of these, “Easter Monday,” ends with an allusion to the angel Gabriel, put to a surprising new use. According to the Bible’s New Testament, he visited Mary and Joseph separately, announcing the birth of Jesus. Like so many of the poems in this book, this one now has a resonance that Rogers could not have foreseen:

Listen! Are we, any of us,

anything but brief appearances

in each other’s lives? As

Gabriel to the unsuspecting Mary,

to Joseph (in that smaller,

more restrained meeting), aren’t

we also miracles, we who wear

no visible wings, announce

nothing more portentous than love?

—Reviewer Frank Beck and Raleigh Whitinger will publish their translation of Lou Andreas-Salomé's 1921 novel, Das Haus, in 2021, with Camden House Books.