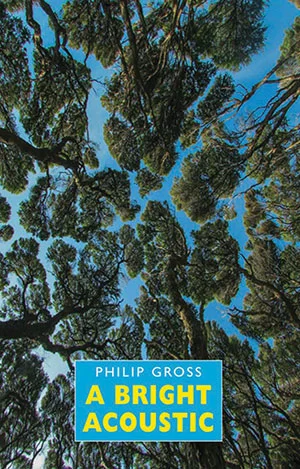

A Bright Acoustic

A Bright Acoustic by Philip Gross. Northumberland, UK: Bloodaxe Books, 2017. 94 pp. £9.95. (paperback)

Philip Gross’s poems are beautiful hybrids of elegy and ode, gentle but insistent pokes of attention to an ecological world, a biome where the human footprint is visibly, audibly present, but in our place—a sea-borne wind farm, orange streetlamps that are part “mist / and its solution,” country motorways through gardens of green. Gross gives us the post-Fall garden of beauty and concern, our footprints are here, our heartprints too, but not as if the world is ours but more like we are its, as fragile a part as the bees or swallows or the gray on gray sky. It is a stunningly, delicately etched collection of poems.

From the first poem, “Windfarm at Sea,” to the last, “Written on Light,” Gross dazzles. His poems, as the volume title suggests, trigger our senses, sight and sound most frequently and immediately. The first poem begins:

Wind flowers

in the mist

as if dark-grown, as spindly as whims,

off the grey coast where there’s no horizon

but one we infer, where they walk

or, sleepwalk, in their middle distance

of just-possibility.

From “Written on Light”:

Beyond the pier this morning,

a pure dazzle – only, in it, silently,

the come and go of white sails,

right to left and left to right,

translucent, barely distinct

from the depthlessness they move in

--slight geometries and intersections

of it in the stillness, just perceptibly

filling or flexing. Beyond our gravity

there are craft, (there are, already)

that ride on the breath of the sun,

the mere pressure of light.

This poem echoes the first, both in the quoted section above and as it continues, but also connects with other poems in the collection—the poem “Agnes Martin,” for example, which is part of the sequence “Specific Instances of Silence”—in its “slight geometries and intersections / of it in the stillness” calling to mind Ms. Martin’s brilliantly subtle canvases—the geometry, the stillness, the depthlessness and the intersections where:

she laid the wash of calculation, concentration,

contemplation on, dissolving them

in space. A hundred shades of silence.

Hung them in a white room, white on white.

One feels certain that the connectedness within this volume is not limited to its pages but extends to the body of Mr. Gross’s work, making further exploration of it something between desirable and urgent. But to stick to this particular volume. The twenty-seven poems in this collection include three extended sequences and multiple smaller sequences—all superb, particularly “Time in the Dingle,” “The Same River: Thirteen Variations on Heraclitus,” “Specific Instances of Silence,” “Blackbird, Descending,” and “Ten Takes on the Garden.”

In “Time in the Dingle” the title of the poems in the sequence are the first line. In one, Gross writes,

It takes me out

of myself, he would say. Stopped

mid walk, mid step almost, following

each chink of sound, all at once

to its several source.

The unseen.

Spreading out, the spaces in him,

between thought and thought and

himself, into a great

dispersion.

When the time comes, scatter me.

This request for a post-life scattering becomes like the dissolving horizon, a way of being here and not here, a way of continuing and being done. “The unseen.”

Mr. Gross’ topics and themes are diverse but never separate—whether it is Heraclitus or Martin, Rodin and his model in “Danseuse Cambodgienne,” a broadleaf chanteuse and her torch song, music and math, nature and art, stillness and movement, life and its moments that fade into the distance—things come together in understanding, in our perceptions and receptiveness, in our interdependent fragility and endurance.

In his poem about Rodin’s early 20th century drawings of the dancer from Cambodia, Mr. Gross begins in stop-time motion, “…whom Rodin, sixty-six / and stiff already, caught – not her but // windrush in her wake” and continues on a quick journey that finds Rodin himself “a blur” and she:

Is smoke. She flares.

Is wind. Is almost

hypothetical. Is nothing.

but a footnote, him

a footnote to the footnote,

to the real thing, the dance.

This is an exquisite observation about life’s transiency and life’s meaning—the living. Life is breath, our wind, “the breath of the sun,” filling the sails of our being, powering us “right to left, left to right,” not meaninglessly but as our contribution to this enduring whole, which is the real thing.

Gross is well-known and well-honored (the 2009 T.S. Eliot Prize for The Water Table) in his homeland, the United Kingdom, but barely known in the United States. A visit to Poet’s House in lower Manhattan and its library of poetry books only resulted in my finding two of his many collections on their otherwise generous shelves. The Manhattan Review (Volume 18, Numbers 1 and 2) has published his work, including one of the above-mentioned sequences from A Bright Acoustic, “Specific Instances of Silence,” but he is a poet who deserves a much greater audience on the world literature stage.

—Reviewer Rick Larios is a reader and occasional writer who lives in Brooklyn with his wife, Cara. He reads because it saved his life as a child growing up on the West Side and he'd be a fool to stop now.