Lessons with Scissors

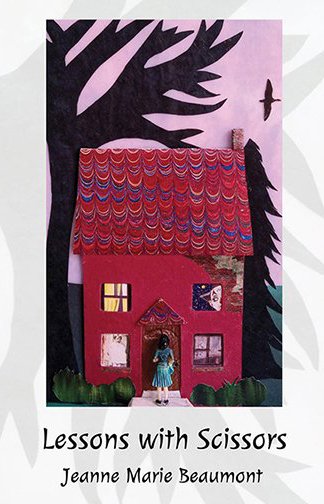

Lessons with Scissors, by Jeanne Marie Beaumont. Rochester, New York: Tiger Bark Press, 2024. 71 pp. $18.95 (paperback)

Lessons with Scissors is Jeanne Marie Beaumont’s fifth book, and this is old home week for many of its poems, which came out first in The Manhattan Review. She has also seen her verse play acted on the stage and is a visual artist known for collages and assemblages—an interest which shows up in the book as “Bebe Marie” where Joseph Cornell’s doll figure gets inside a viewer’s brain

I always mean to write tougher reviews, but one way or another the poets catch me off-guard. Beaumont’s wordplay disarmed me. Anyone who can write “as the redundant pundit put it” or begin a poem “the broom will now kiss the bride,” and end it “The groom will now kiss the bridge,” has my number. Like Robert Lowell, she tweaks or places clichés so they come awake. The examples quoted are from Curious Conduct (2004), an earlier book, more playful and audacious than the one under review. But Beaumont still has words on the brain, even if the puns and turns of wit are employed more subtly.

This isn’t light verse—far from it. In fact, some of her distinctiveness derives from the combination of wordplay with gravitas, or darker emotions. The domestic modernism of Lessons with Scissors speaks of houses, relationships, personal moments in elusive language that has a bite, especially in two poems which capture the experience of Catholic School. All to the good. The time has long passed when poets could describe a family photo in workshop-worn diction, evoke a vague nostalgia and feel like another poem was in the books.

These poems are distant, self-contained, with neither denial nor inflation of feeling, neither stylized weariness nor exuberance, an achievement, since a spirit of “Goodbye to all that,” pervades the book, appropriate for a poet born in 1954 and writing when so much that seemed solid ground is sinking beneath our feet. More dead people (dead in the legal, medical sense) than what William Burroughs once referred to as “so-called real people” appear in these poems—naturally enough; as we tread life’s winding path, those gone before take on a luster, a fascination denied to those we rub elbows with every day.

Two works especially evoke a generational awareness—We shall not pass this way again. In “Table Four” (p. 77) the familiar experience of eavesdropping on a party of nearby diners takes four paragraphs, each made of generic restaurant phrases and activities linked by ellipses: “One asks for decaf,” Guess who I heard from, “a single dessert arrives with four spoons…” But each paragraph also has a phrase more deeply universal: the order of death for those at the table is included. “(And one of them will die first)”; “(And one of them will die next)” “Table Four” seems strong and fresh—not grim, just casting a cold eye on life and death.

Arranged in couplets given impetus by enjambment, “End of an Epoch” is another piece that caught my attention. The speaker, again, foregrounds the generic, dramatizing the belated discovery that we may have exaggerated our uniqueness. “Our” story may be the story of a cohort. Beaumont scores a perfect image for her theme: “…the way that Lara toward the end/ of Dr Zhivago plods down the dull Soviet street/ becoming smaller and less distinguishable in the frame,/ her glamor hidden in a dumpy cloth coat, soon/ to be lost in the century that is swallowing her./ “ (p. 80) Why perfect? First, it’s an image from a movie—not nature or private experience. Movies bond a generation. And Dr. Zhivago! Only seven films have been seen by more people. Julie Christie! That enigmatic smile, wistful and seductive, as she fixes the opium pipe in McCabe and Mrs. Miller. This is extraneous to Beaumont’s theme, but for such an avatar to disappear into the century!

The second strophe looks back at what the ego has surrendered: “But what is this self-life we carry about in our crania,/ this one that feels so important today to feed and// encourage and propel forward to prevail, although/ just one among billions of like-minded hardheads,//”

However, lest we think “Fading Into the Epoch” a manifestation of conventional Buddhism, (the fading is social, historical, not cosmic) a final turn transcends, resolves the conflict by affirming the generation. “what a pretty epoch it was at times, such vibrant colors// and delight of forms, so many voices still speaking// tenderly that floated upwards…” Anticlimax alert—I’m not sure I understand the closing thought—those voices floating upwards become “inaudible/ as the wind rushed in and stripped the trees.” Does that mean those lasting voices of our (actually a decade older, I am grandfathering myself into Beaumont’s epoch) generation are erased by the historical defeat of so many hopes? “The light at the end of the tunnel was a train coming the other way.” And wind stripping the trees is too bleak for Beaumont to simply be evoking the way voices of an era melt into the era. Oh well, a poem should not mean but be (wonder if that old-timer still makes the anthologies). Still, “Epoch” is such a limpid, balanced, articulate piece—and touches important issues if you feel as I do that narcissism is the Achilles heel of lyric poetry--also an indispensable prerequisite—and Beaumont does a good job of keeping narcissism on a leash without choking it.

Beaumont also likes to use some sort of formula to generate pieces: “A Mad Woman’s Multiple Choice” (p. 36) is set as a multiple-choice quiz, the various answers a mentally ill woman might give to a prompt. “Don’t touch a. my hair I am not your puppet/ b. my food I will refuse to eat it/ c. my papers my soldiers will cut you into pieces.” “Since” (p. 20) has the word since in a column out to the side of a list of phrases which might begin or end with since—“ it’s a first offense,” “ever” and others more complex. A Brief Index of the Life and Private History of Emily Jane Bronte (1928) is a kind of found poetry. Apparently the index from a biography, it makes a portrait of the subject. “clothes, ugliness of, 82, 95/ colossal loneliness, 50/ Dark Hero, 50ff, 55, 56, 89,…/Byron as, 113-115…” This practice, a verbal parallel to Beaumont’s work in collage and assemblage, suggests underground rivers of imagination flowing beneath the borders of a chosen professional métier.

I hope I’ve given an idea of Beaumont’s range and the unities beneath. For all her fear of fading into the century, these are not generic poems—though readers should decide that question for themselves. They won’t regret it.

—Lem Coley is a retired English professor living on Long Island.